About brittle unit tests

On March 18, 2023

As software engineers advance in their careers, they will come to realize that software systems are dynamic and can evolve in unpredictable ways over time. It's a fact of life that can't be avoided. That's why having strong refactoring skills is one of the most valuable abilities a developer can possess. Refactoring, term which was coined by software engineer Martin Fowler, is the process of making changes to the internal structure of software, making it easier to understand and more cost-effective to modify without altering its observable behavior.

What may seem like a good organization of components and types on a given system at any moment can become questionable in a short amount of time. That's why continuous refactoring is necessary to ensure the system's maintainability and prevent the natural decay that occurs when additional features are added.To support refactoring, it's important to have a comprehensive set of test suites, including unit, integration, and system tests. These tests play a vital role in verifying that any changes made during refactoring don't cause unintended consequences or regressions in the system's functionality. By consistently applying these best practices, developers can enhance their codebase's readability, reliability, and scalability over time. Ultimately, these skills will help them stay ahead of the curve and be well-equipped to face the ever-evolving landscape of software development.

The problem

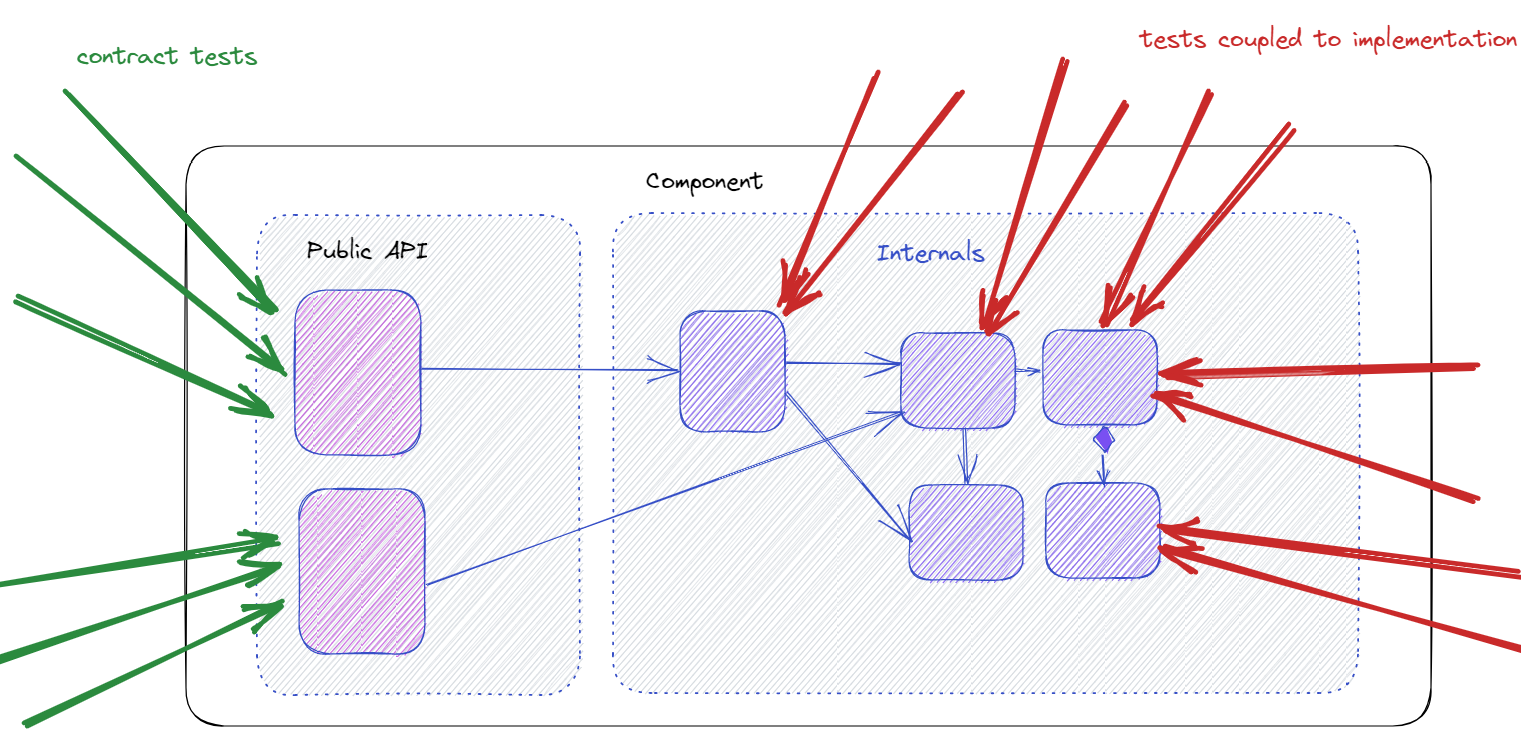

The following can be stated regarding unit tests: The depth of refactor a given test suite safely allows is inversely proportional to the coupling to the system under test internals. While an extract method might be free-lunch, Inline class will probably produce a cascade of broken tests. So, a good test suite should enable easy refactor. The question is, how to achieve this? What are the trade-offs to be taken? Let's evaluate with a very common style of tests, primarily seen in older code bases:

public class UserService : IUserService

{

public UserService (IUserValidator userValidator, IUserRepository userRepository, IMessageBus messageBus)

{

....

}

public async Task<Result> AddNew(string name, string id, string email){

var user = new User {

Id = id,

Name = name,

Email = email

};

if( userValidator.IsValid(id, name, email))

return Result.Fail("Invalid user");

if(await userRepository.Exists(id))

return Result.Fail("Invalid user");

await userRepository.Add(user);

await messageBus.Notify(new NewUserCreated(user));

await userRepository.Save();

return Result.Success();

}

}

public class UserValidator : IUserValidator {

public bool IsValid(string id, string name, string email){

if(name.Length > 25){

return false;

}

....

}

}

The code above follows the classic approach of monolithic services and anemic domain models, where the domain objects are passive structures, and the services are responsible for all the application logic. This style of code can lead to tightly coupled and hard to maintain codebases, especially as the application grows and new features are added.

To make matters worse, related tests tend to heavily mock and check the interactions between collaborators, which can make them brittle and prone to breaking when the implementation changes:

Remember that tests are a crucial aspect of the codebase, and they should be created in a way that adds value and minimizes maintenance expenses in the long run. They shouldn't act as an obstacle to code evolution by generating false alarms or rework during minor code changes.

[TestClass]

public class UserServiceTests

{

public UserServiceTests ()

{

_userValidatorMock = new Mock<IUserValidator>();

_repositoryMock = new Mock<IUserRepository>();

_messageBusMock = new Mock<IMessageBus>();

_sut = new UserService(_userValidator.Object, _repositoryMock.Object, _messageBusMock.Object);

}

[TestMethod]

public async Task<Result> CantAddNewWithInvalidName(){

string invalidName = "someInvalidName";

_userValidatorMock.Setup(x => x.IsValid(It.IsAny<string>(), invalidName, It.IsAny<string>())).Returns(false);

var result = _sut.AddNew("123",invalidName, "anEmail@mail.com");

Assert.Equal(result, Result.Fail("Invalid user"));

}

[TestMethod]

public async Task<Result> ValidUserIsSaved() {

string newUserId = "123";

_userValidatorMock.Setup(x => x.IsValid(It.IsAny<string>(), It.IsAny<string>(), It.IsAny<string>())).Returns(true);

_repositoryMock.Setup(x => x.Exists(newUserId)).ReturnsAsync(false);

_repositoryMock.Setup(x => x.Add(It.Is<User>(x => x.Id = "123"))).ReturnsAsync(true);

_repositoryMock.Verifiable();

var result = _sut.AddNew(newUserId, "aName", "anEmail@mail.com");

_repositoryMock.Verify();

}

[TestMethod]

public async Task<Result> UserIsVerified() {

string newUserId = "123";

_userValidatorMock.Setup(x => x.IsValid(It.IsAny<string>(), It.IsAny<string>(), It.IsAny<string>())).Returns(true);

_repositoryMock.Setup(x => x.Exists(newUserId)).ReturnsAsync(false);

var result = _sut.AddNew(newUserId, "aName", "anEmail@mail.com");

_userValidator.Verify();

}

.....

}

Although it may be tempting to disregard these tests as a weak argument, they are actually quite prevalent in web applications. The London testing school is a whole movement that advocates for this type of testing, where you verify a unit's behavior by confirming who they communicate with among their collaborators. However, there is a problem: the code is so intertwined with its dependencies that any modification will put you back to square one, without any tests to support your changes.

[TestClass]

public class UserValidatorTests

{

[TestMethod]

public async Task<Result> ItRejects_UserWithNameTooLong() {

string aLongName = "aVeryLongNameThatShouldProduceAnError";

var sut = new UserValidator();

Assert.False(sut.IsValid("1", aLongName, "aValidEmail"));

}

....

}

A possible solution

It can be argued whether the inclusion of IUserValidator as part of the public API of this service layer is necessary or simply a matter of complying with SOLID principles. However, the presence of outbound adapters to out-of-process dependencies (database repository and message bus) is unquestionable. Regardless of whether the inclusion of IUserValidator is a good idea, it appears to be a type that is entirely owned by the application and could potentially be passed as a real dependency.

There are two benefits to decoupling tests to interaction verification with a particular type: tests become more reliable as they exercise more code, and the code becomes less resistant to refactoring. However, we still need to maintain mocks that go beyond the process boundaries. The trade-off is that the UserService tests will now need to have an awareness of the UserValidator's behavior to set up proper test scenarios.

[TestClass]

public class UserServiceTests

{

public UserServiceTests ()

{

_repositoryMock = new Mock<IUserRepository>();

_messageBusMock = new Mock<IMessageBus>();

//We pass a real UserValidator into the tests.

_sut = new UserService(new UserValidator(), _repositoryMock.Object, _messageBusMock.Object);

}

[TestMethod]

public async Task<Result> CantAddNewWithInvalidName(){

//This is knowledge leaked from the UserValidator class

string invalidName = "someInvalidName";

var result = _sut.AddNew("123",invalidName, "anEmail@mail.com");

Assert.Equal(result, Result.Fail("Invalid user"));

}

}

Step 1: Remove owned dependency mocks by real instances.

The advantage of decoupling the test from a mock configuration is that it reduces coupling, which is a positive thing. Additionally, the test is no longer coupled to the IUserValidator abstraction, and it is instead verifying behavior from the perspective of the API consumer. As a result, we can continue moving user validator tests, which are implementation details, to the public API, specifically the application service.

[TestClass]

public class UserServiceTests

{

....

[TestMethod]

public async Task<Result> CantAddWithANameTooLong(){

//This is knowledge leaked from the UserValidator class into the UserServices tests; the name is too long.

string invalidName = "aVeryLongNameThatShouldProduceAnError";

var result = _sut.AddNew("123",invalidName, "anEmail@mail.com");

Assert.Equal(result, Result.Fail("Invalid user"));

}

}

Step 2: Move tests related to the IUserValidator to the Service tests and remove flaky tests - eg: "UserValidatorIsInvoked"

We still are using the UserValidator, but all the behaviour is now checked from the perspective of the user service API; Indeed, tests have been moved from implementation details to the public contract of the class, and they're no longer concerned about the interactions with this type. At this point, we're in a good situation to refactor, removing the UserValidator so user's behaviour and data is properly encapsulated as following snippet demonstrates:

public class UserService : IUserService

{

public UserService (IUserRepository userRepository, IMessageBus messageBus)

{

....

}

public async Task<Result> AddNew(string name, string id, string email){

try

{

var user = User.Create(id, name, email);

if(await userRepository.Exists(id))

return Result.Fail("Invalid user");

await userRepository.Add(user);

await messageBus.Notify(new NewUserCreated(user));

await userRepository.Save();

return Result.Success();

}

catch (UserNameTooLongException)

{

return Result.Fail("Invalid user");

}

}

}

public class User {

private User(string id, string name, string email ) {

//setters

}

public static User Create(string id, string name, string email){

ValidateNameLength(name);

....

return new User(id, name, email);

}

public void ValidateNameLength(string name){

if(name.Length > 50){

throw new UserNameTooLongException();

}

}

....

}

Of course, the tests need a small tune-up: We need to remove the UserValidator inyection in the system under test constructor, but that's it. Ideally, instantiation of the sut should be delegated outside of the test itself.

Certainly, like all software engineering solutions, there are trade-offs to consider when making decisions. In this particular case, we sacrifice the granularity-conciseness of tests related to UserValidator, as they are moved to the consumer APIs. A few conclusions to finalize:

-

By substituting real objects for mocks and removing the need for interaction verifications, we can achieve a decoupling of tests from implementation.

-

When we move the testing of any implementation detail related concerns to the service's public API, any service method that uses this type will need to re-implement these tests. This approach is beneficial for tests-as-documentation purposes, but ultimately increases the number of redundant tests.

-

Generally speaking, tests become more coarse-grained and black-boxed, which requires a bigger and more complex "arrange" phase.

-

When inyecting real dependencies instead of mocks, initialization ceremony might be more complicated. In our example,

UserValidatorclass is trivial to instantiate. This is not always the case. Besides, their detail will leak into the consumer class tests. Ultimately, this is what enables safe refactor of the class. -

Depending on your application's boundaries, you may need to move tests to a different layer. For example, the user's maximum length tests could be part of the

Usertype in a domain layer. However, adding such tests will increase coupling to the code, so it's a matter of choice as to what approach is best for your application.

Feel free to comment! Until the next post.